The world’s population is set to reach nearly ten billion by 2050, with over six billion people projected to be living in urban areas. With an uptick in urban growth, this shift is already well underway, too, including in the MENA region, which is currently undergoing a period of rapid urbanisation.

To accommodate this growth without exacerbating inequality, environmental degradation, pollution and public health problems, urban spaces need a rethink.

Here, instead of being a driver of destruction and division, the built environment can be used as a tool for recovery, sustainability and inclusivity.

Rapid growth and investment an opportunity for transformation

One lens through which to view this space transformation is placemaking, an approach to urban planning and design which centres community and localised solutions to create places that serve the people that live in them.

Advocates say it’s a vital tool in the MENA region, which is both on the front lines of the climate crisis and witnessing significant investments in infrastructure and development.

Ethan Kent, Executive Director of PlacemakingX, is one of these advocates.

Kent co-founded the organisation back in 2019 with the aim of connecting and supporting placemaking advocates and practitioners to accelerate collective learning, advocacy and action.

Since its inception, the organisation has helped launch nearly thirty regional placemaking networks worldwide.

According to Kent, in the MENA, placemaking is an opportunity to focus and define public spaces around core values and local culture, building on local assets and practices.

“It’s a way to leverage the significant investments that are going on in infrastructure and development in the MENA region for public goals and to layer more purpose and meaning onto some of the spaces that are being created very quickly, that perhaps have not yet integrated with the local context.”

Indeed, the region is currently witnessing a construction boom, with a planned US$2 trillion in construction projects. But, according to Kent, while the MENA is seeing significant investment in this area, the region is in danger of replicating the mistakes of the West.

“The most unsustainable way cities are growing, even with green design and green infrastructure, is that they sprawl,” said Kent, explaining that this is not only unsustainable environmentally but also economically.

“The biggest mistake American cities have made is how they’ve sprawled and built roads and created a dependence on infrastructure that is bankrupting many small towns and cities that can no longer afford to sustain the infrastructure.”

Echoing this call for change is Sébastien Turbot, Director of Content Development at the non-profit policy research and advocacy centre, Earthna, established under Qatar Foundation (QF) to inform and influence national and global sustainability policy.

Turbot noted that cities are central to the climate change conversation, being both part of the problem and the solution, especially in hot and arid environments which suffer from increasing heat, aridity, water scarcity, growing food insecurity, and poor air quality.

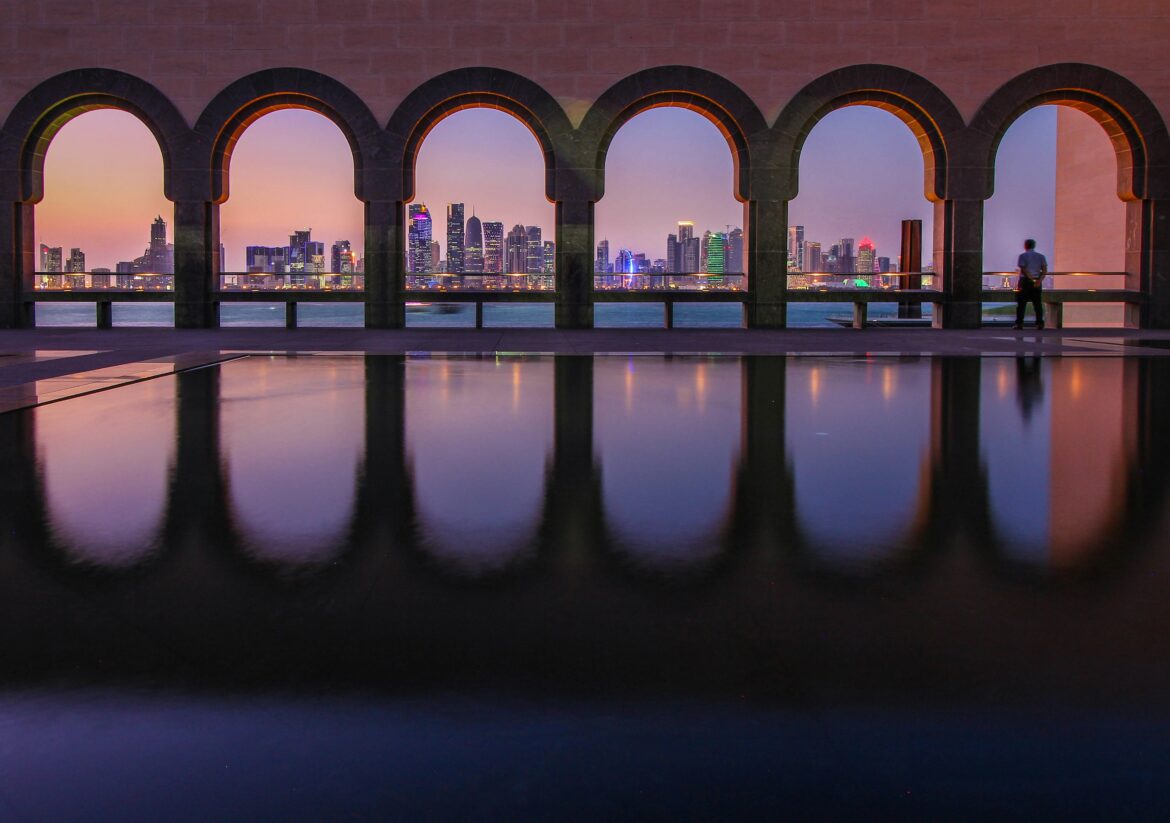

“We want to help our capital city of Doha and other cities to identify and find solutions to these issues,” said Turbot.

Creating the roadmap for change

According to Turbot, who leads Earthna’s stream on cities and the built environment, evidence-based research is the foundation of place transformation.

As such, the non-profit recently launched a six arid city study to assess the challenges and needs of different geographies.

Turbot explained that based on this research, Earthna plans to launch an arid cities network through which solutions and best practices can be shared.

“To our knowledge, there is no specific platform or convening power focusing on hot and arid cities,” said Turbot.

Indeed, creating spaces that make sense in the regions in which they are situated is key, as is building awareness and community engagement within cities, another step highlighted in Earthna’s action roadmap.

Here, Kent noted that when envisioning new spaces, sustainability should go beyond ecological considerations.

“It’s about building the capacity and connections within communities to work together to address issues, to build resilience, not just ecological resilience but social resilience.”

Adding: “When people are attached to their place when they become part of the placemaking process, they create these virtuous cycles of contributing to place and benefiting from it, giving back in ways that create further local culture, local economies, local health.”

Beyond this, policy is central to creating the frameworks to facilitate change, and here, Turbot shared a number of policy priorities, including:

-Innovative architecture and urban design to create low-density areas with less car-centric sprawl,

-Encouraging alternative technologies, whether renewable energy systems, integrated multimodal transport systems, or retrofitting existing buildings – all according to local climatic conditions,

-Driving education and awareness,

-Encouraging urban and peri-urban agriculture, and

-Conserving and rehabilitating natural habitats and ecosystems.

The solutions of the past in the contemporary context

Alongside these policy priorities, Turbot spotlighted the importance of making the most of existing solutions and taking inspiration from local heritage. Indeed, Earthna, a play on words referencing both ‘Earth’ in English and إرثنا, the Arabic word for legacy, places great emphasis on utilising solutions from the past.

“We think that continuing to find new solutions to contemporary problems is important, but we also feel it’s important to look back to the past and see how cities were designed and built before, and if there’s something we can learn,” said Turbot.

Here, Turbot explained that the world’s first cities were also born in the region, seen in the urban settlements of Mesopotamia, where inhabitants harnessed wind and shading to battle hot temperatures.

Replicating such techniques in contemporary contexts is vital in a region like the MENA, where air conditioning accounts for a significant portion of energy consumption. In the GCC, for example, air conditioning makes up around 70 per cent of annual peak electricity consumption.

According to Kent, it’s these small changes that can have a profound impact.

“A lot of the best placemaking actually doesn’t cost a lot,” explained Kent.

“It’s about adding some seating and some shade; it’s small things that make a big difference in the comfort and connection that people have in a community.”

Here, Kent also noted the importance of achieving sustainability systemically, in a way that’s comfortable for people and anchored to the local economy, identity, culture and heritage.

One hot-topic concept which also has deep historical roots in the region is the 15-minute city, which is increasingly being proposed as an urban planning solution that addresses many of the challenges associated with modern living.

The concept focuses on providing people with the services and amenities they need, within only a short distance from their homes, bringing together communities and reducing emissions.

“The traditional Arab Medina is a perfect example of this idea of the 15-20-minute city,” said Turbot, who cited Msheireb in Doha as a contemporary example of this in action.

A mixed-use space, the area is completely walkable, offering a wide range of amenities. Further, as an innovation district, it blends both tech-based solutions, such as sensors for energy efficiency, with more traditional solutions that utilise shade and wind.

“No one’s saying that we should completely destroy cities and rebuild from scratch, but every 20 or 30 years, you will get an opportunity to rethink and redesign specific neighbourhoods,” said Turbot.

“This is where policymakers, residents, and businesses need to really leverage that opportunity, to rethink and redesign these districts into 15-20 minute neighbourhoods that are great spaces to live, work and play, but are also much more sustainable than more recent kinds of city building approaches,” he added.

Realising placemaking’s potential

Moving to new models of urban design and building that centre both people and the planet is essential as temperatures soar, populations grow, and vital resources become increasingly scarce.

However, Turbot noted that many cities and national governments are not necessarily equipped to meet these challenges.

“It’s really urgent that we develop environmentally, socially, and culturally appropriate approaches, including hybrid forms.”

Kent believes placemaking can be the lynchpin tying this all together: “In settlements, inherently less habitable to humans, placemaking is all the more needed to make them livable, to focus efficient development around, and to further guide and grow their sometimes contested identities,” said Kent.

Yet, according to Turbot, due to the extreme temperatures engulfing the MENA for six months of the year, placemaking has often been seen as a “nice to have” but not necessarily adapted to the region.

Aiming to shift this perception and address the lack of understanding of the concept and its potential, Earthna recently curated a three-day Placemaking Program in Doha, in which Kent was involved.

The program hosted discussions, workshops, and networking sessions for international thought leaders and local stakeholders that focused on cross-cutting agendas to shift culture within government and engage communities for greater inclusivity.

“We really felt that we needed to push the envelope to get to that tipping point,” said Turbot.

Now, he said, a shift is taking place: “We really feel that we now have the momentum to build on and to leverage that to bring in a wide array of actors here locally in Doha to more meaningfully engage in rethinking urban spaces.”

Meanwhile, looking ahead, Kent shared his hopes for the World Urban Forum in Cairo in November 2024, which he sees as an opportunity to gather placemaking leaders from the region and centre discussions on the value of public spaces.

“It’s an opportunity for the region, which is fast developing, to develop around public spaces,” said Kent.

“This is a pivot point to turn upside down the shaping of cities and start with public spaces and the people that are there and attract investment and define design and development in ways that support public spaces and local place identity.”

By Madaline Dunn, Lead Journalist, ESG Mena